In the fight to lower veteran suicide, stress during the transition to civilian life is an overlooked risk factor.

By. A.M. Hammond

As the War on Terror ramped up after 9/11, Dustin Yates — then 19 years old and bored with community college in Tampa, Florida — joined the Army because he wanted to do good for others.

He joined the Special Forces and quickly became devoted to protecting his fellow soldiers. His mother, Carol Collier, said he felt survivor’s guilt as soon as he returned from his first combat deployment. He didn’t like thinking of another soldier having to take his place, she said.

Then, after almost a decade of service, Yates was unexpectedly discharged following a DUI. He took it hard because he loved the military, said Collier, 61. Still, Yates had received an honorable discharge and had an upbeat outlook as he began the transition back to civilian life.

Yates returned to community college, hoping to “give back,” he told his mom, by becoming an engineer and improving access to clean water in areas affected by American military operations. He supported himself during school by stocking shelves at Target.

But just two years after leaving the Army came another devastating blow: Yates took his own life. He was 32 and no one saw it coming. His death shocked his mother, their family and his fellow soldiers. “He always seemed happy,” she said. “He just hid everything very well.”

Yates’ plight illustrates what experts call transition stress. More than a dozen experts, from officials at Veterans Affairs and the Army to psychologists and suicide researchers, as well as veterans and survivors of veteran suicide, have all described how the transition to civilian life is a vulnerable time for veterans who are already hesitant to ask for help.

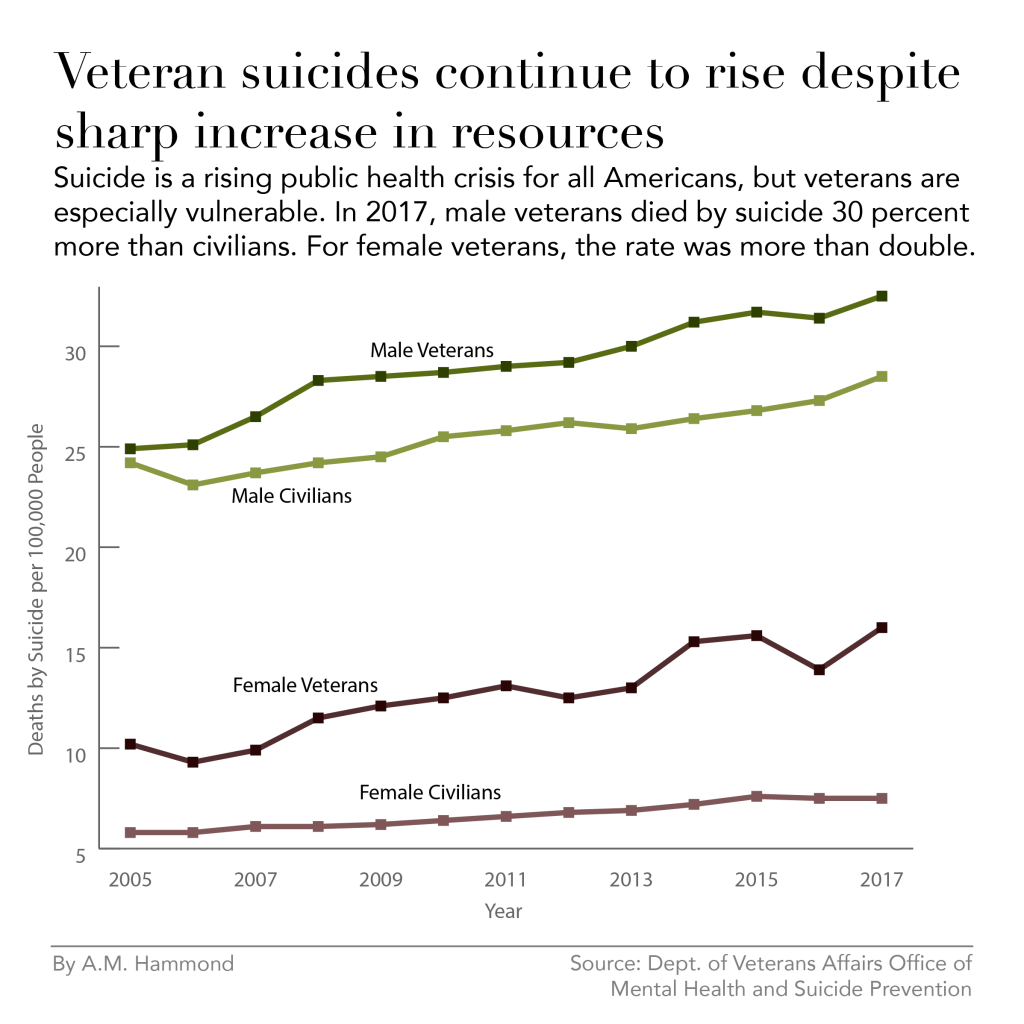

Veterans of the Armed Forces are 50 percent more likely to die by suicide than civilians, according to the VA . But in their first year after separation from the military, that risk doubles, compared to the overall veteran population.

About 200,000 servicemembers separate from the military every year. In 2017, the most recent year for which data is available, more than 6,000 veterans took their own lives — averaging 17 deaths per day.

Two out of three veterans who die by suicide hadn’t been to a VA facility in the two years before their death. As a result, Secretary of Veterans Affairs Robert Wilkie has called for a public health-based, community-wide outreach, enlisting the help of employers and religious and health care organizations.

But getting veterans to ask for help, no matter from whom, may be one of the biggest obstacles. Studies have shown up to 50 percent of veterans with significant mental health symptoms have not sought treatment. And while PTSD and traumatic brain injury have justly been the focus of extensive research in the quest to reduce veteran suicide, the stressors of separating from service have been underappreciated as contributing factor.

Transitioning to a new phase of life can be extremely stressful for everyone. Entire textbooks have been devoted to the subject. Anyone who’s moved to a new city, left for college, started a new career or even returned home from prison can relate.

But for veterans — who come from a highly regimented environment that also provides deep camaraderie and a profound sense of duty and respect — that sense of alienation and unmooring is amplified. According to experts, this stress can put veterans at risk for depression, anxiety and even suicidal thinking.

Chelsey Wilks, a psychologist and suicide researcher at Harvard who has worked with veterans for many years, says the loss of identity and structure of military life can be overwhelming: During active duty, soldiers “are told when to eat, what to eat, what to wear, what to do. They have a close-knit group of friends. They have a purpose,” she says.

When they come home, “all of that kind of structure and purpose and the daily regimen that they were used to is gone. And all of the sudden they have to make a lot of decisions, and they have to kind of create a whole new life worth living for themselves.”

Even veterans who don’t have a history of mental illness can struggle with finding meaning and purpose in a new civilian identity, and experts say that transition stress itself is common.

Dustin Yates had to make life-and-death decisions during his time in the Army, his mother said.

“He had a lot of responsibility in the military. And then he gets out of the military and he goes to work at Target and his biggest responsibility is making sure there’s enough cans of beans on the shelf.”

An increasing problem for younger veterans

The first person to jump off the San Francisco Golden Gate Bridge was a World War I veteran in 1937, said Kate Mostkoff, a suicide prevention coordinator at the Manhattan New York Harbor VA.

Eighty years later, there is more scientific understanding, less stigma and more mental health resources for veterans dealing with emotional struggles. In 2019, the VA budget called for $9.4 billion to expand access to mental health care for veterans. And yet the rates of veteran suicide show no signs of abating.

Suicide is not only a veteran issue. It’s on the rise for almost every demographic in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it’s the 10th leading cause of death in America.

In 2017, male veterans died by suicide nearly 30 percent more often than their civilian counterparts, and female veterans died by suicide at more than twice the rate of female civilians.

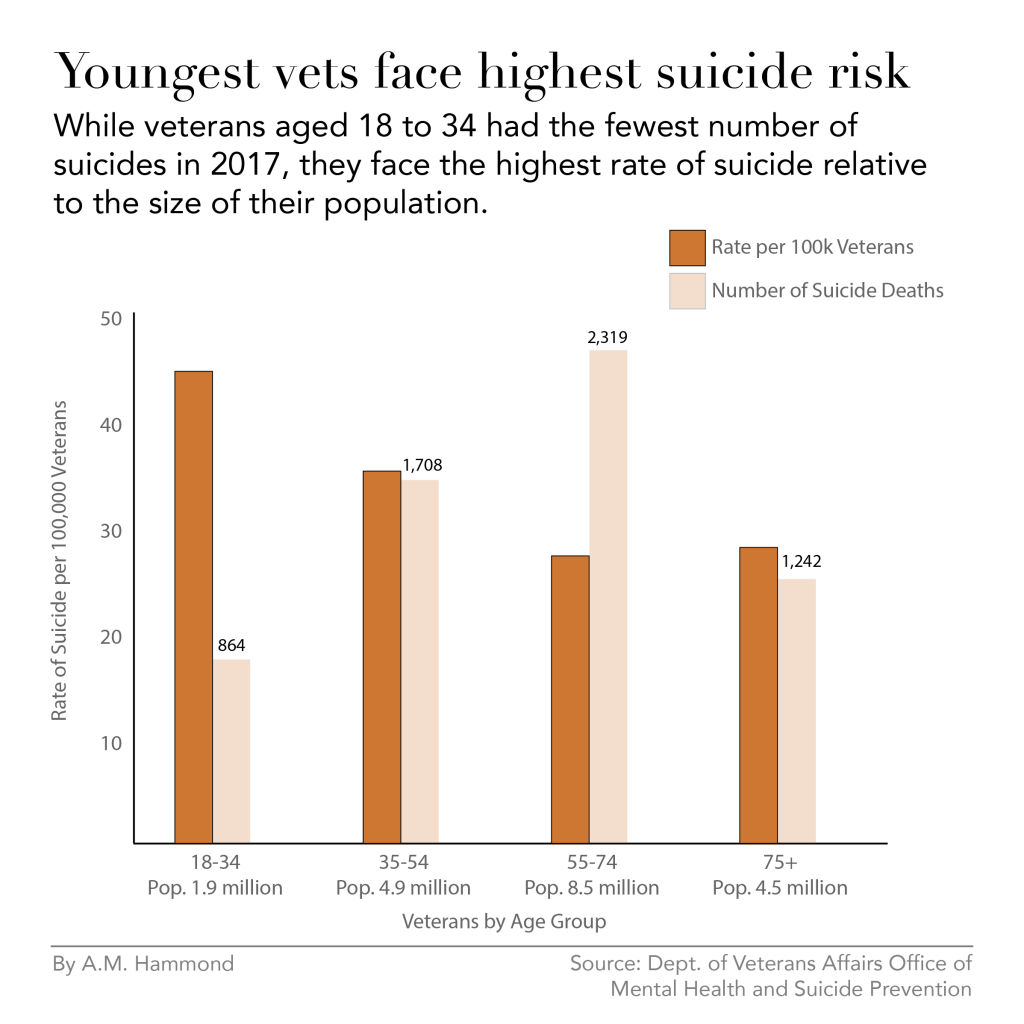

Vietnam veterans between the ages of 55 to 74 experience the greatest number of suicides. But it’s the youngest veterans, aged 18 to 34, who are dying by suicide at the highest rates. Their risk is 65 percent higher compared to older vets.

A dangerous separation

Researchers have shown that combat deployment did not increase the risk of death by suicide for soldiers who served in Afghanistan and Iraq. What did increase the risk of suicide was separation from service, and that risk was even higher for soldiers who served less than four year or who separated with less than honorable discharge.

The study authors said it was possible the transition to civilian life could increase risk for suicide: “Loss of a shared military identity, difficulty developing a new social support system, or unexpected difficulties finding meaningful work may contribute to a sense that the individuals do not belong or are a burden on others.”

In other words, when their lives stop revolving around the military, returning veterans feel like outsiders and struggle to relate to civilians, even loved ones. Many mourn the loss of respect and purpose they once felt during service but now lack in civilian jobs.

According to Wilks, the military suicide researcher from Harvard, the largest predictive factor of veteran suicide is the unemployment rate in given zip code.

To that end, the Department of Defense has made a Transition Assistance Program, commonly referred to as TAP. “Transitions support looks at military service members as co-workers, and is geared toward helping service members in transition find their next paid job,” said Shauna Springer, a psychologist who worked with veterans directly at the San Diego VA for eight years.

TAP includes a week of workshops on things like writing resumes, how to get through a job interview, even how to start a small business.

But Springer says there are more fundamental challenges ahead: “Psychologically, it’s a very different issue. What we’re talking about is people losing their entire attachment network, their tribe or family,” she says.

“A lot of people in the military build a sense of family and bonds with people that are hard put into words, and it gives structure and meaning to their life,” Springer says. “It gives them a role and it’s integrally related to their sense of purpose.”

In transition, suddenly, that tribe is lost, and some veterans may face an identity crisis as a result, she says.

“No one should say that everybody faces transitions stress,” she says, but many veterans “are going through a process of transition that’s intensely stressful. And it’s a vulnerable time.”

And that’s not a topic that’s discussed during the TAP training.

Lacking understanding or respect

Ian McCall served for four years on full active duty in the Marines, as an infantryman in a helicopter assault unit in Iraq. His battalion fought in the Battle of Ramadi, which had some of the highest causality numbers of any battle during the Iraq War.

When he came back to the States, McCall said it was like coming back to a different world. At age 24, he enrolled at Emory University in Atlanta, where he said he found it hard to relate to other students, partially because of his age, but also because of his combat experience.

One day in a business class, a professor asked students what they should do about an employee who excels in some areas but doesn’t do great in others. McCall’s classmates said the employee should be fired or punished until they did everything perfectly.

McCall disagreed. He gave the example of another soldier on his unit who was in some ways a mess: often late, often disheveled, occasionally drunk even, he said.

“But when it came to actually deploying and doing what needed to be done, he had the highest body count in the battalion,” he told the class.

“The whole auditorium of students froze and the professor was like, ‘Oh my god, did you just say body count?”’ McCall said. Then room erupted in nervous laughter.

Many veterans feel disrespected and misunderstood when they leave the military, said Wilks. They also face anti-veteran stigma, she said, which makes them feel like outsiders in their own communities.

“It’s like being a wolf and coming back into an environment where everybody’s pugs and designer dogs,” McCall said. “You’re tapped into your most primal instincts, and you’ve got claws and you’ve got fangs.”

“Some people are scared of you. Some people see you as a novelty. But at the least, you’re never going to be able to roll over and play fetch as well as everybody else.”

“Everybody just seems like they’re moving so much more slowly than what I was used to,” McCall said of the civilian life. “In the Marines especially, there’s a uniformity of execution and thought.”

Back home, he said, people did things however they wanted, and seemingly without thought. “People are walking through Walmart pushing carts and they don’t look where they’re pushing them. [I was] getting pulled over and messed with because I ran stop signs.”

“It just seemed like it was so much red tape,” he said. “There were so many rules and so many fragile people and so many unwritten rules.”

“It wasn’t that I was depressed. It’s just that military life, everything is so — you live life in such extremes, that nothing out here really measures up.”

McCall said he was able to be himself at group therapy sessions at the local VA, which helped his mental health. But he still struggled at times, alternating between pushing himself to the limit to succeed and then just shutting down completely when he would hit a wall.

In times of overwhelming frustration, he said sometimes he thought about suicide, partially because he said the military had changed his relationship to death.

“We write our first wills out when we’re 18 years old,” he explained. For veterans, he said, “when it comes to the possibility of our death, it’s not this thing that sits so far off in this realm that we can never imagine. It’s a possibility that never leaves.”

A culture of strength

McCall has mixed feelings about the help he’s received at the VA. But at least he went.

There are two kinds of barriers to mental health treatment. One is structural: A person lives too far away, or they can’t afford care, or they’re too busy. But the other barrier is harder to tackle, what Wilks calls “attitudinal barriers”: Someone thinking, “I can handle the problem myself” or “I don’t want people to think I have a mental health problem.”

Even as the VA continues to work on increasing access to mental healthcare, this stigma, or fear of stigma, prevents veterans from seeking the care they need. And the numbers reflect that: Two out of three veterans who died by suicide in 2017 had not been to the VA for care in the previous two years.

Just this December, the VA announced a new program in collaboration with the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security, called Solid Start, that will reach out to new veterans three times within the first year of their separation.

While the VA has spent billions of dollars hiring additional mental health clinicians to shorten wait times and increase access, they can’t help veterans who don’t show up.

“Men are socialized from birth to hide and master their emotions,” says Wilks. “Then the military is like, ‘Don’t show emotion, because that’s a sign of weakness.’”

Major Chaplain Bruce Duty says there is always a mental health provider, whether a psychologist or social worker, that accompanies combat units, in addition to a chaplain.

Duty is currently stationed at the Fort Hamilton Army Garrison in south Brooklyn. The Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, where a number of people die by suicide every year, looms large and graceful over the low-slung buildings dotted around the base.

He says both chaplains and mental health workers stay busy talking to soldiers during deployments, especially after combat events, but that there is still a fear of being seen as weak for seeking care.

“Soldiers will go to behavioral health, but they cover their faces and hope no one else sees them,” he says.

But many avoid the therapist’s office altogether.

“Service members are aware that mental health providers serve in a dual role where assessing for troop readiness is a consideration that they carry along with the wellbeing of the service member,” said Springer.

In other words, what a soldier tells a therapist is not always confidential. If a provider feels a soldier’s symptoms may put the unit in danger, the provider is required to notify military leadership, which soldiers worry could jeopardize their careers. Soldiers then carry that mistrust with them when they transition to civilian life, creating another barrier to mental health care.

Chaplains, however, have no such obligation, and as a result can serve as de facto therapists for deployed soldiers.

“It’s the only safe place for [soldiers] to really open up. So the chaplains carry a lot of pain of a lot of people as a result,” Springer says.

It’s no surprise, then, that the chaplaincy recognizes the significant part it has to play in suicide prevention, intervention and postvention — the term for helping survivors cope with the loss of a fellow soldier or loved one to suicide.

It’s usually chaplains who provide the suicide prevention workshops soldiers are required to attend each year. The workshops cover the warning signs of suicidal thinking: giving away possessions, drafting a will, serious alcohol abuse.

Because the soldiers hear a similar schtick every year, Duty tries different techniques to keep it fresh and to really try to break through the stigma of seeking help.

He starts his 40-minute workshops by naming very successful people: Beyoncé, Terry Bradshaw, Buzz Aldron. “What do all of these people have in common?” he asks during presentations. “They struggled with their mental health. And they asked for help.”

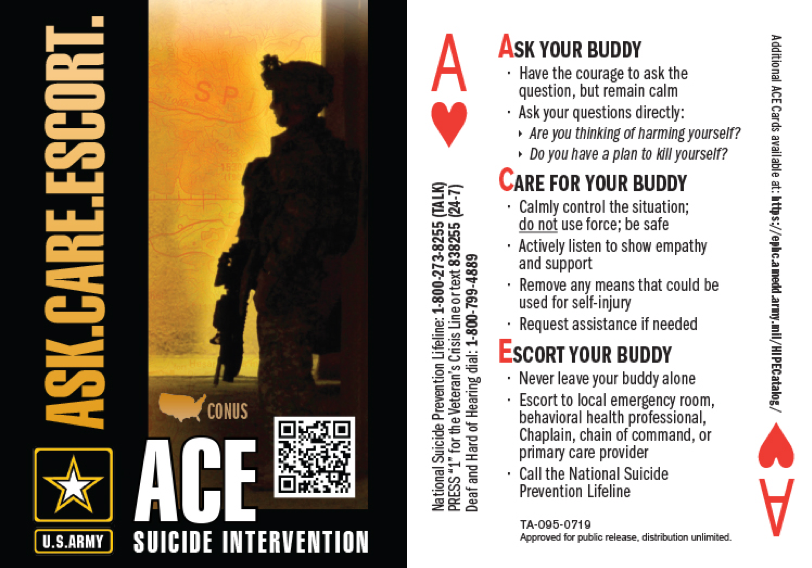

They also cover how to help one another in times of distress, using the helpful acronym ACE: Ask. Care. Escort.

One of the greatest sources of support soldiers have is one another, Duty said. Going through “the suck” together — waking up at the crack of dawn, going through strenuous training, serving in combat — doing all these things together creates deep bonds and brotherhood.

But the chaplain was at a loss when asked how the Army prepares soldiers who are preparing to “ETS” — short for “expiration – terms of service” — to find new sources of support in civilian life.

“It seems like an obvious question, but we’re not asking it yet,” he said.

Every day a struggle

Carol Collier said she cried every day for the first six months after her son’s death.

“I remember the six months because it was so profound I wrote it on the calendar,” she said.

Three years later, she says it’s still difficult to muster the motivation to get up in the morning or want to do anything.

“Every day is a struggle,” she says.

Soon after his death, an active-duty friend recommended Collier reach out to the nonprofit TAPS, the Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors. The organization provides 24/7 grief counseling and peer support for families and loved ones of active duty soldiers and veterans who have died while serving or as a result of their service.

The staff at TAPS take their work personally. Nearly every member of its staff has lost a loved one who served in the Armed Forces; a few are are veterans themselves.

Collier was connected with a survivor support team, who checked up on her regularly in the weeks and months after Dustin died. She also got connected with other family members who’d lost loved ones to suicide.

“Everybody is in different in places in their grief. But you still know that they know, they understand,” she said. “If they start saying something and you start crying, you don’t have to apologize. They don’t apologize. It’s okay. You know that.”

Even with this support network, though, Collier was having difficulty processing her grief, so TAPS connected her with HomeBase, a clinic in Boston that helps veterans and their families recover from the “invisible wounds” of war like traumatic brain injury, PTSD and transition stress.

She attended a two-week intensive program of group and individual therapy, eight hours a day. She said it really helped her deal with her feelings of guilt, which are common after a loss to suicide.

She also got a cat about a year after her son’s death, and said it has been an enormous source of emotional support. During a phone interview, she said her feline companion had been perched up on her chest. “He’s the most affectionate, lovable little guy,” she said.

“Far left of bang”: A new kind of boot camp

Collier and veteran Ian McCall both said that soldiers need more support from the Department of Defense in re-entering civilian life.

“They’re so programed to change their whole lifestyle to be that soldier, that I think they need to do something when they come out to de-program them, to program them back to civilian life,” Collier said.

McCall likened this kind of transition preparation to the briefings soldiers get before entering a combat zone. “We could go into [transition] understanding, like, what you’re about to go into, man, it’s gonna be crazy,” he said.

But, McCall said, “the only problem with that is that once something is mandated, then it’s got to be executed at a high level.”

Shauna Springer, the former VA psychologist and now the senior suicide prevention coordinator at TAPS, understands firsthand both the challenges veterans face returning home and the difficulty in implementing help on a broad scale.

To that end, in November, along with retired Army Lieutenant Colonel Jason Roncoroni, Springer published “Beyond the Military: A Leader’s Handbook for Warrior Reintegration,” which provides a “roadmap” for successful transition. It gives advice about long-term, meaningful career development, but also “whole health,” culture shock and family adjustment.

“It’s also looking at how do they create a plan for themselves to socially integrate into their new neighborhoods? Because the military is such a small and shrinking population. It’s necessary for transitioning service members to find ways to create new tribes,” Springer says.

Springer made certain to point out the handbook is not meant for suicide prevention. Rather, “what we are doing is trying to get far left of bang” — a military expression meaning upstream prevention.

“Take a case of two people. One of them, 18 to 24 months in advance, builds a roadmap for their future life after the military that is aligned with their values. And they start to look for possibilities in their career and in their social life.”

“That person is on a totally different trajectory, as far as suicide risk, than somebody who doesn’t prepare, and then loses their attachment network and feels isolated and alienated in a culture that has values that are very different from their own.”

Springer hopes the book will end up in the right hands of military leadership and eventually become a supplement to the current Transition Assistance Program, as a tool soldiers read and work through individually to plan ahead holistically for civilian life.

“When people are coming into care, that means that they’re really struggling with something, that they’re really challenged by something. If you can go far upstream from there, and provide them with a roadmap that allows them to fulfill their potential and socially connect with a new tribe, then maybe they won’t ever have to enroll in the VA.”

Carol Collier makes certain to say she doesn’t blame the VA or the military for her son’s death. “There may have been help out there for him and he didn’t seek it,” she said. But that’s exactly why she thinks soldiers need more guidance before returning home.

When veterans get back, she says, “they’re going to think they have it under control because that’s what the military teaches them.”